The History of the Car Radio

1906: Music is heard on air

1920: The first U.S. radio broadcast license granted

Though Fessenden’s broadcast caused a wave of excitement, it took 14 more years for the first commercial radio station to be born. On October 27, 1920, KDKA in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, obtained the first broadcast license. About a week later, on November 2, they aired the results of the Harding-Cox presidential election. The nation was enchanted, radio stations proliferated, and radio became America’s new favorite form of entertainment.

1922(ish): The first car radio debuts

Naturally, entranced listeners wanted to take this new form of entertainment with them on the road. So not long after commercial radio broadcasting was born, the first car radios began to appear. The early history of the car radio, however, is a little unclear. Legend has it that George Frost, an 18-year-old radio enthusiast from Chicago, was the first person to attach a portable radio to the passenger door of his Ford Model T. No one knows if it’s actually true, but it makes for a good story anyway.

1930: Car radios go commercial

Although commercial car radios hit the market in the late 1920s, it wasn’t until Galvin Manufacturing Company (now known as Motorola) introduced the Motorola 5T71 radio that commercial car radios really became popular. (See the complete story on Motorola next)

Seems like cars have always had radios, but they didn’t. Here’s one of the story’s:

One evening, in 1929, two young men named William Lear and Elmer Wavering drove their girlfriends to a lookout point high above the Mississippi River town of Quincy, Illinois, to watch the sunset. It was a romantic night to be sure, but one of the women observed that it would be even nicer if they could listen to music in the car. Lear and Wavering liked the idea. Both men had tinkered with radios (Lear served as a radio operator in The U.S. Navy during World War I) and it wasn’t long before they were taking apart a home radio and trying to get it to work in a car.

But it wasn’t easy: automobiles have ignition switches, generators, spark plugs, and other electrical equipment that generates noisy static interference, making it nearly impossible to listen to the radio when the engine was running. One by one, Lear and Wavering identified and eliminated each source of electrical interference. When they finally got their radio to work, they took it to a radio convention in Chicago. There they met Paul Galvin, owner of Galvin Manufacturing Corporation. He made a product called a “battery eliminator”, a device that allowed battery-powered radios to run on household AC current. But as more homes were wired for electricity, more radio manufacturers made AC-powered radios. Galvin needed a new product to manufacture. When he met Lear and Wavering at the radio convention, he found it. He believed that mass-produced, affordable car radios had the potential to become a huge business. Lear and Wavering set up shop in Galvin’s factory, and when they perfected their first radio, they installed it in Galvin’s Studebaker. Then Galvin went to a local banker to apply for a loan. Thinking it might sweeten the deal, he had his men install a radio in the banker’s Packard. Good idea, but it didn’t work, half an hour after the installation, the banker’s Packard caught on fire. (They didn’t get the loan.) Galvin didn’t give up. He drove his Studebaker nearly 800 miles to Atlantic City to show off the radio at the 1930 Radio Manufacturers Association convention. Too broke to afford a booth, he parked the car outside the convention hall and cranked up the radio so that passing conventioneers could hear it. That idea worked – He got enough orders to put the radio into production.

WHAT’S IN A NAME

That first production model was called the 5T71. Galvin decided he needed to come up with something a little catchier. In those days many companies in the phonograph and radio businesses used the suffix “ola” for their names – Radiola, Columbiola, and Victrola were three of the biggest. Galvin decided to do the same thing, and since his radio was intended for use in a motor vehicle, he decided to call it the Motorola. But even with the name change, the radio still had problems: When Motorola went on sale in 1930, it cost about $110 uninstalled, at a time when you could buy a brand-new car for $650, and the country was sliding into the Great Depression. (By that measure, a radio for a new car would cost about $3,000 today.) In 1930, it took two men several days to put in a car radio. The dashboard had to be taken apart so that the receiver and a single speaker could be installed, and the ceiling had to be cut open to install the antenna. These early radios ran on their own batteries, not on the car battery, so holes had to be cut into the floorboard to accommodate them. The installation manual had eight complete diagrams and 28 pages of instructions. Selling complicated car radios that cost 20 percent of the price of a brand-new car wouldn’t have been easy in the best of times, let alone during the Great Depression. Galvin lost money in 1930 and struggled for a couple of years after that. But things picked up in 1933 when Ford began offering Motorola’s pre-installed at the factory. In 1934 they got another boost when Galvin struck a deal with B.F. Goodrich tire company to sell and install them in its chain of tire stores. By then the price of the radio, with installation included, had dropped to $55. The Motorola car radio was off and running. The name of the company would be officially changed from Galvin Manufacturing to “Motorola” in 1947. In the meantime, Galvin continued to develop new uses for car radios. In 1936, the same year that it introduced push-button tuning, it also introduced the Motorola Police Cruiser, a standard car radio that was factory preset to a single frequency to pick up police broadcasts. In 1940 he developed the first handheld two-way radio– The Handy-Talkie for the U. S. Army. A lot of the communications technologies that we take for granted today was born in Motorola labs in the years that followed World War II. In 1947 they came out with the first television for under $200. In 1956 the company introduced the world’s first pager; in 1969 came the radio and television equipment that was used to televise Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the Moon. In 1973 it invented the world’s first handheld cellular phone. Today Motorola is one of the largest cell phone manufacturers in the world. And it all started with the car radio.

WHATEVER HAPPENED TO the two men who installed the first radio in Paul Galvin’s car? Elmer Wavering and William Lear, ended up taking very different paths in life. Wavering stayed with Motorola. In the 1950’s he helped change the automobile experience again when he developed the first automotive alternator, replacing inefficient and unreliable generators. The invention lead to such luxuries as power windows, power seats, and, eventually, air-conditioning. Lear also continued inventing. He holds more than 150 patents. Remember eight track tape players? Lear invented that. But what he’s really famous for are his contributions to the field of aviation. He invented radio direction finders for planes, aided in the invention of the autopilot, designed the first fully automatic aircraft landing system, and in 1963 introduced his most famous invention of all, the Lear Jet, the world’s first mass-produced, affordable business jet. (Not bad for a guy who dropped out of school after the eighth grade.)

Sometimes it is fun to find out how some of the many things that we take for granted actually came into being! AND it all started with a woman’s suggestion!!

The History of the Studebaker Car Radio

Interesting as the Motorola story is, it was Philco not Motorola that was the chosen to be the “Radio Accessory” supplier for Studebaker.

Philco was founded in 1892 as Helios Electric Company. From its inception until 1904, the company manufactured carbon-arc lamps. As this line of business slowly foundered over the last decade of the 19th century, the firm experienced increasingly difficult times. As the Philadelphia Storage Battery Company, in 1906 it began making batteries for electric vehicles. They later supplied home charging batteries to the infant radio industry. The Philco brand name appeared in 1919. From 1920 to 1927, all radios were powered by storage batteries which were fairly expensive and often messy in the home. In late 1930 James M. Skinner, was now the company’s President. Skinner had been the driving force behind Philco’s success for many years; having been responsible for getting Philco into the business of starting batteries, radio batteries, Socket-Power units, and ultimately, radios.

The automobile radio was becoming popular. The Automobile Radio Corporation had been formed in 1927 by C. Russell Feldman to produce Transitone radios for installation in automobiles. The early Transitones had two-dial tuning and took up a lot of dashboard space. Priced at over $150 (like Motorola), they sold poorly. Philco became involved with Automobile Radio Corporation in mid-1930. By August, they were not only selling Transitones through Philco dealers, but they were also building a single-dial unit for Automobile Radio. In December, Philco purchased the Automobile Radio Corporation, creating a new subsidiary exclusively for automobile radio – the Transitone Automobile Radio Corporation. Shortly afterward, Philco introduced a new Transitone auto radio, the Model 3, which was priced below $100.

I solicited information from the Studebaker Drivers Club Forum and the following help was provided. Thanks to both Richard and Roy.

Richard Quinn from the Studebaker Drivers Club Forum:

“Studebaker began to wire their Commander and President closed models for radio in March 1930. This would have been the 1930 models FE and FH Presidents and Commander GJ and FD. The lead wire came through the left front pillar to the chicken wire in the roof which acted as the “antenna.” This would allow for the installation of any brand of radio though at the time Studebaker was not offering a specific brand or model.”

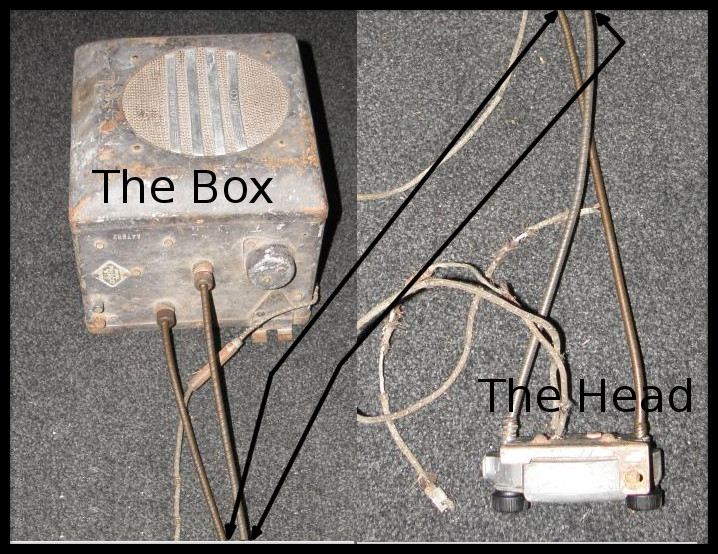

“The first radio offered by Studebaker was a model 7 Philco Transitone officially introduced on June 3, 1931, it was given a part number of AC-3. The head was mounted on the far right side of the instrument panel accessible only to the passenger. The radio box was secured in the center of the firewall.” (Photos above)

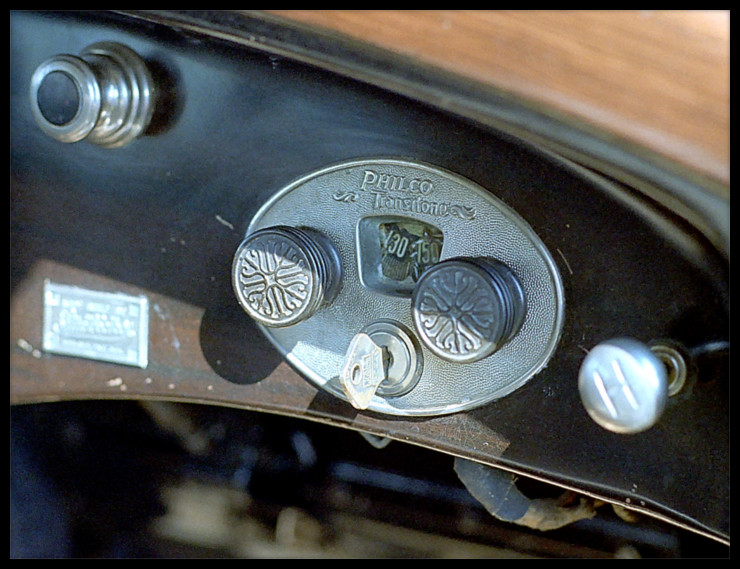

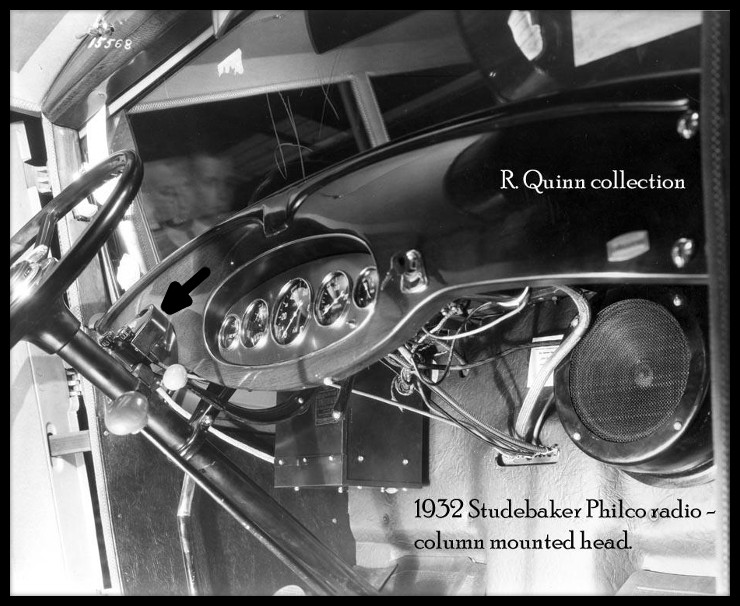

“In April 1932 a new Philco Transitone Super Heterodyne unit was adopted and offered with a steering column mounted head so it it could be operated conveniently by the driver. The price was $69.50 installed ($5.00 more west of the Mississippi). Studebaker continued using the Philco brand right on through the post war years, though Motorola offered a replacement “aftermarket” radio in the late 30s”. (Photo Below)

Radio Roy / (Roy Yost) from the Studebaker Drivers Club Forum:

“For 1931: Studebaker AC-3 is a Philco Transitone model 7, Studebaker AC-4 is a Philco Transitone model 8, and Studebaker AC-176 is a 5 tube Philco Transitone model 6. Studebaker AC-174 is a single unit Philco radio for open cars, Studebaker AC-177 is a six tube Philco Transitone model 9, and Studebaker AC-176 is a 5 tube Philco Transitone model 6. Single unit most likely refers to a model that does not have a separate tuning head connected to the radio with speedometer cable technology. Except for the open cars, my information does not say what car models these fit. When I wrote my unpublished monograph 30 years ago, I used a number of sources. Among these were Turning Wheels articles, Sams Photofacts and Riders perpetual troubleshooters manuals. As far as I know, all factory Studebaker radios from 1931 through 1955 were made by Philco. All 1956 – 1966 Studebaker factory radios were made by Delco. There were some radios marked Transtar that were made by Motorola. These would be for the new dashboard that the trucks got in 1956 or 1957. There were aftermarket car radios built by other companies for almost all of these years”.